Listening Creates an Opening is a multi-site, intermedia performance installation by Mary Armentrout Dance Theater, commissioned by the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) which is hosted on the campus of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI). The work, which is written, devised and directed by Mary Armentrout, takes notions of embodied listening as a lens through which to explore site, history and the artist’s relationship to social engagement. It continues Armentrout’s longterm collaboration with media artist Ian Winters, who produced extended time-lapse multi channel videos / installations and a cloud sculpture for the piece, and features music and 16 channel sound design by composer Evelyn Ficarra. Listening Creates an Opening and was commissioned by EMPAC and supported by their Residencies and Commissions program. The work was premiered 12th – 15th September 2018 at EMPAC.

You can hear an interview of collaborators Mary Armentrout, Ian Winters and Evelyn Ficarra on The Sanctuary for Independent Media WOOC FM about the project here and an earlier interview of Mary Armentrout here.

In short term residencies, taking place over a period of two years (2017-18), Armentrout and the team worked closely with musician / performers Darcy Dunn and Allison Easter (singers) and Patrick Belaga (cellist/improvisor) to create the work. Interdisciplinary artist Chris Evans also collaborated in the early development stages of the piece, taking part in the artist residency at EMPAC in April 2017, and her contribution as is strongly felt by the team. Evans and Ficarra now have a music duo (cello and live electronics) which has developed its own life and trajectory outside this project.

Listening Creates an Opening is a multi-site, site-specific work, which explores various localities at EMPAC and beyond. The piece travels from a small common room on the RPI campus, to a hillside outside EMPAC, to the EMPAC theater (where audience are seated on the stage) and then wanders through town via a parking lot and a hair salon, ending up for the final scene in a video installation at the Hudson River at sunset.

The sound for the piece consists in two main elements: scored music (for two singers and cello) and sound score (for two videos, a light sculpture, and a theater scene).

For the scored music, Ficarra wrote settings, and fragments of settings, of two short poems by Emily Dickinson, scored for different combinations of two singers and cello, which Armentrout cut up and wove around her text. The poems (In this short life and If I can stop one heart from breaking), chosen by Armentrout, delicately interrogate ideas of human agency and the meaning; and the purpose and fleetingness of life. These sung / played fragments formed a kind of loose sonic netting for the work, sometimes seeming to form part of the internal monologue of the main performer, sometimes working as structural touchstones or set pieces.

To create the sound score, Ficarra worked with several hours of field recordings she had made in the EMPAC building, around campus and in town, and with material developed in recording sessions with the singers and cellist.

In particular, sounds and improvisations recorded with cellist Patrick Belaga became central to the sound design for the video pieces and cloud sculpture.

In addition, in Spring of 2018, Ficarra gave a workshop to the students of Nina Young‘s class ‘Exploring Music at RPI’ in the huge stairwell at EMPAC which featured in Ian Winters’ yearlong time-lapse film.

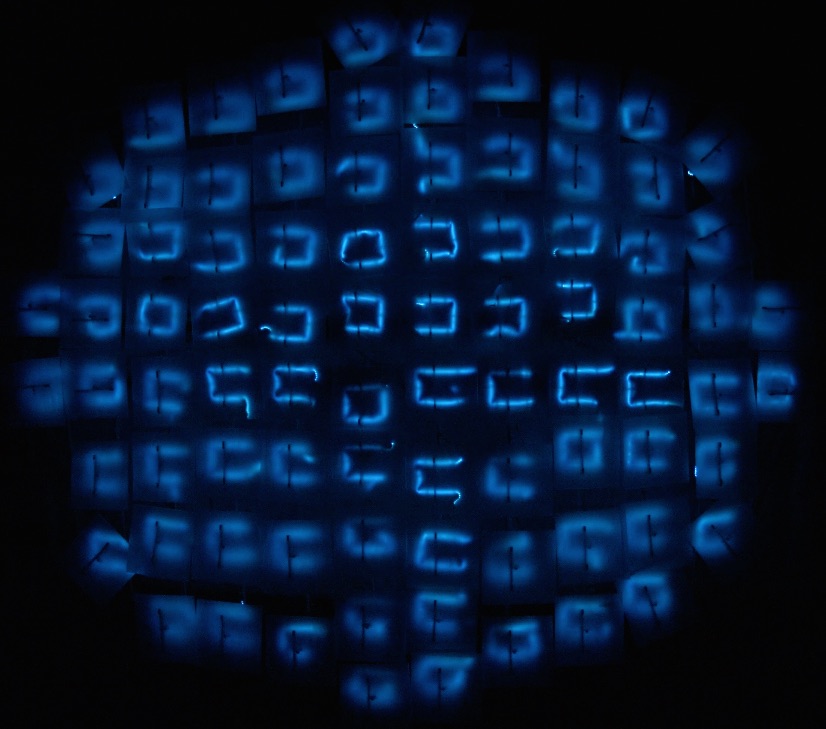

Using the Emily Dickinson poems as material, she recorded multiple group vocal textures with the students as performers – whispering, humming, intoning and whistling. These textures formed a vital element of the sound score for Ian Winters’ cloud sculpture, made out of LEDs.

Ian Winters’ cloud sculpture used, as a source for changing light, over a year’s worth of data collected from light and colour sensors set in the roof of the EMPAC building. The 16 channel sound for this section combined sonic references to both sites visited in the show and to the music within it, creating an immersive sonic environment which the audience experiences by lying down under the cloud.

The sound for the cloud was a particular challenge – how to relate to this technological abstraction, whose flashing lights animated a year’s worth of captured data from light/color sensors embedded in the EMPAC roof? One way would have been to sonify the same data, and Ficarra might take this path at a later point for future versions of the piece. For this iteration it seemed more important to explore notions of capture and abstraction, creating a soundscape of highly processed abstracted sounds whose origin is only dimly intimated. She worked extensively with the sound recordings described above, using digital processing, layering and editing, deploying the sounds across 16 speakers in the theater space, and sometimes re-recording these soundscapes and further manipulating them. Part of the challenge was to develop movements for the sounds in space that could be discernible for listeners lying on their backs on the floor… this picture shows the cloud sculpture hanging over the stage in the EMPAC theater.

… and the view from underneath….

Excerpt from cloud soundscape:

Here’s a river view taken one night at our final scene….